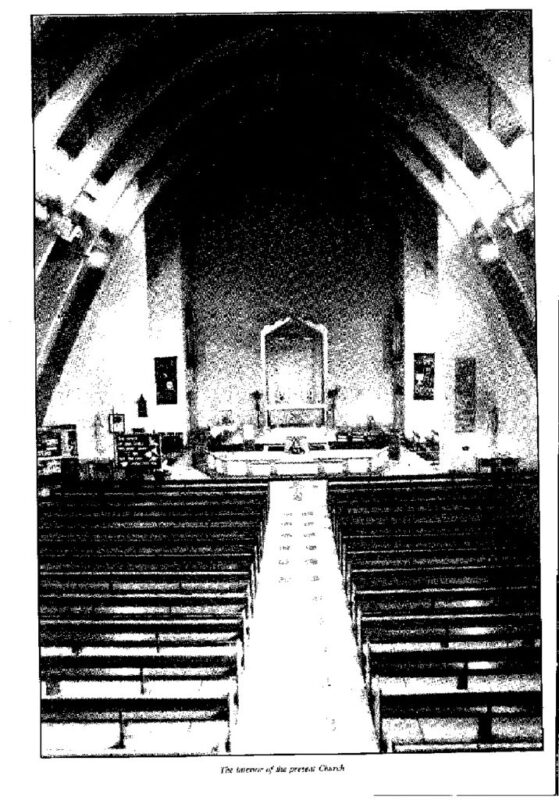

The church is dramatic parabolic arched church of the late 1950’s with an almost industrial aesthetic, whose power comes from its pre-cast reinforced concrete arches which support the clerestory. Its powerful interior is not to be missed – best seen from the West end gallery which should be open. This church was needed to provide more extensive and suitable accommodation in an area with much new housing and migration from Ireland in the 1950’s. It was built in 1960-61 to modern, but pre-Vatican II, design ideas. The architect was David Stokes, who was the son of Leonard Stokes (architect not just of telephone exchanges but of the Anglican London Colney convent to which Ninian Comper added a chapel in the 1920’s, a current Society case). David Stokes actually designed the church as early as 1955-6. His only other significant churches seem to have been Our Lady of Walsingham also at London Colney (1959) and rebuilding of Holy Name, Bow Common after bomb damage.

As Robert Proctor says in Building the Modern Church “its exterior was municipal in style, resembling a theatre or swimming pool”. At Greenford the intention was explicitly to eliminate aisles and columns and to allow a broad rather than a long nave. At the west end there is a single storey narthex. To the North West a tall, gaunt campanile without even a cross on it rears above an opening between the church and the adjoining school. The parabolic arches are marked externally on the south side by small, low brick buttresses, while on the north (street) the feet of the arches are exposed. Some polychromatic detailing in an inappropriate ‘Butterfieldian’ style using darker bricks to contrast with the red brick was added in the 1990s by D. W. Aitken, to replace square concrete panel cladding, which had apparently failed.

The western part of the sanctuary is lit by a mesh of small rectangular windows with white and bright yellow glazing. A similar mesh forms a large west window but here the panels are coloured very light blue. The most dramatic stained glass are the strips of very thin multi-coloured glass either side of the nave which have quite an ethereal effect on a sunny day with blues, greens, yellows, oranges and purples dominant (and is an original feature supplied by James Hetley & Co). In the nave there is a clerestory on either side formed of a continuous row of clear glazed rectangular panels with aluminium frames and brick piers, 1990s replacements for square concrete framed openings. The internal walls are rendered and are painted off-white or cream. A small Blessed Sacrament chapel is located behind a glazed screen on the north side of the sanctuary (an addition since consecration). The organ pipes are inserted into plain niches either side of the Sanctuary. The confessionals (two on either side) are pleasingly designed with slightly bowed out vertical oak boarding.

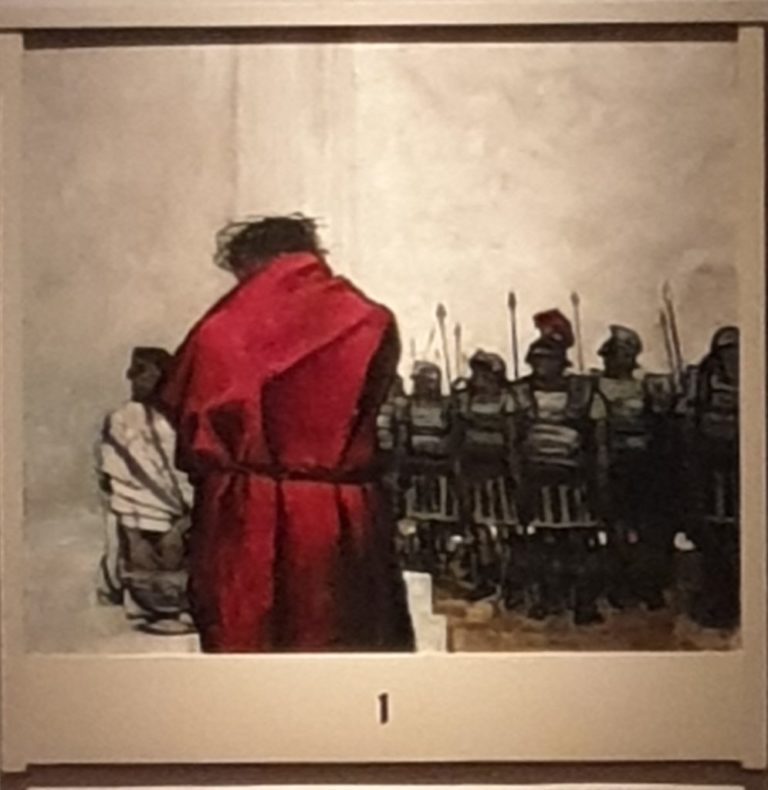

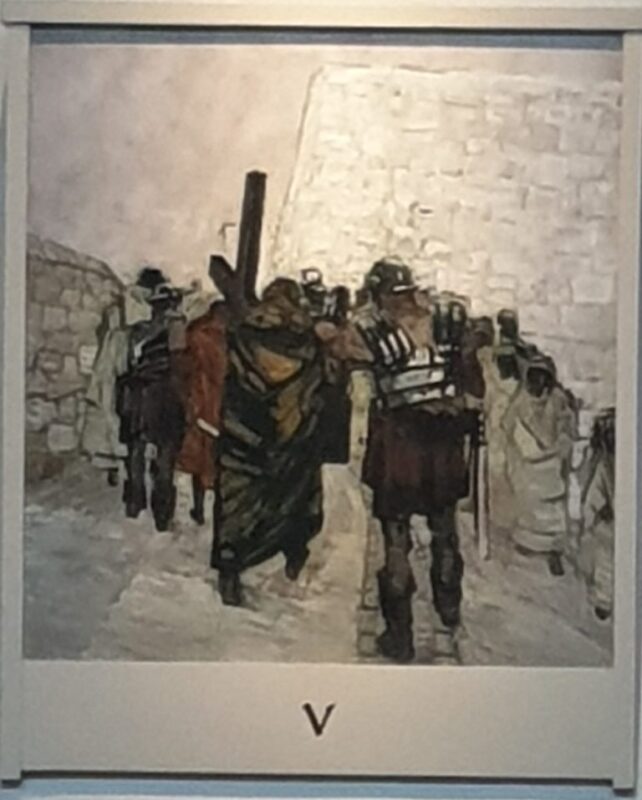

Our Lady of the Visitation, unusually for a Catholic church, was written up in the architectural press, specifically in the Builder 19 January 1962. It describes the aluminium baldachino, partly finished with gold leaf and from which hung a Perspex canopy, no longer there. The article goes on to say that this was lit by three lights concealed at the back which also threw beams of light on the High altar of Cornish granite (still there as are statues of Christ and Mary, Queen of Heaven, either side of the sanctuary but I do not know who the sculptor was). The paintings of the Stations of the Cross were commissioned from Philip Le Bas and date from 1960 or 1961.

How was David Stokes and his client, the parish priest, able to push through to consecration such a modern church as early as 1961,when the then Archbishop (Godfrey) was a real conservative in terms of style? Godfrey demanded that architects submit to him detailed drawings of liturgical fittings and according to Building the Modern Church Stokes was quizzed in particular about the altar and baldachino and told to show the parish priest a similar built example (at London Colney). When Heenan became Archbishop of Westminster in 1963 there was much greater acceptance of modern design as Vatican II reforms also began to make themselves felt. Nonetheless this is a remarkable church for its date and deserves to be better known.